Vaccines are one of the most profound ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF BIOMEDICAL SCIENCE.

Smallpox has been eradicated. Three infectious agents (polio, measles, rubella) have been targeted for elimination by the World Health Organization and another seven have been at least 90% eradicated in the U.S. largely due to the efficacy of vaccines. But it has not been possible to create vaccines for some of the most important infectious diseases. We aim to create vaccines for such difficult targets and to devise new strategies to enable vaccine generation. Our vaccine targets include HIV-1, pandemic influenza, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

Our research is primarily focused on eliciting antibody-mediated immune responses. There are known monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that can provide broad protection against HIV-1, pandemic influenza, and Ebola – but generating vaccines that elicit antibodies with properties of these mAbs has not been possible. Accordingly, a major goal of our research is to devise new protein engineering strategies to enable immunofocusing – the creation of vaccines capable of eliciting an antibody response against a targeted epitope.

Our studies interrogate the viral neutralization properties of mAbs and antisera from immunized animals. We also investigate antigen-antibody interactions using biochemical, biophysical, and structural biological methods. We aim to understand the somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation following vaccination by isolating and sequencing individual human, non-human primate, and murine B cells.

The COVID-19 pandemic shows how highly effective mAbs can quickly be rendered ineffective against new emerging viral variants that contain amino-acid substitutions in the epitopes of the mAbs. We introduced a new class of broad-spectrum virus inhibitors, called ReconnAbs, that tether the ectodomain of the cell’s viral receptor (ACE2 in the case of SARS-CoV-2) to a non-neutralizing, highly conserved antibody (which, in theory, is less likely to be subject to immune pressure because the epitope is non-neutralizing). We aim to establish ReconnAbs as potential therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2 and other emerging infectious pandemic diseases.

As a complement to our experimental protein engineering efforts, we use machine learning algorithms known as protein language models to successfully reconstruct protein evolution landscapes through local predictions of evolutionary velocity (evo-velocity). Remarkably, the same principles can be used to guide artificial evolution. We have performed language-model guided affinity maturation of diverse mAbs with high efficiency using protein sequence information alone. We anticipate that language models will become a key part of the protein engineer’s toolkit and seek to further enable these methods. We also aim to uncover potential insights into natural evolution provided by the success of this approach.

Immunofocusing

Over recent decades, many monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with potent and broad-spectrum neutralizing activity against certain viruses have been isolated and characterized. Several of these broadly neutralizing mAbs (bnAbs) have been shown to prevent and/or treat infections in animals humans. The discovery of bnAbs reignited major efforts to create vaccines against important pathogens that have evaded conventional vaccine approaches, including HIV-1 and pandemic influenza.

Various “immunofocusing” strategies have been employed in attempts to elicit a polyclonal antibody response toward a specific epitope. Nonetheless, to date, it has not been possible to create a vaccine that elicits a bnAb-like response. A major challenge in vaccine development, therefore, especially against rapidly evolving viruses, is the ability to focus the immune response toward evolutionarily conserved antigenic regions that have been shown, with mAbs, to confer broad protection.

A major goal of our research is to develop and implement immunofocusing methods to enable generation of vaccines that address major unmet medical needs.

These methods include a new immunofocusing strategy, antigen reorientation, accomplished by site-specific insertion of aspartate residues (oligoD) into antigens to facilitate their binding to alum adjuvants. We applied this approach to an H2 HA to create an “upside-down” configuration on alum, which sterically occluded HA-head while exposing HA-stem to the immune system (Fig. 1). Immunization with this reoriented H2 HA (reoH2HA) induced a stem-directed, cross-reactive response in mice to diverse HAs from both group 1 and group 2 influenza A subtypes. The simplicity of oligoD-based antigen reorientation will enable and accelerate the development of epitope-focused vaccines against many other viruses and infectious agents.

We also utilize structure-guided design of vaccine candidates with hyperglycosylation that aims to direct antibody responses away from variable regions and toward conservative epitopes of an antigen. In this manner, we have introduced a universal Ebola virus vaccine approach aimed at conferring cross-protective immunity against the three species that have resulted in human Ebola outbreaks: Zaire, Bundibugyo, and Sudan viruses (Fig. 2).

We introduced a method for creating epitope-focused vaccines called PMD (for protect, modify, deprotect). The steps for PMD are: (i) protect an epitope on a protein by binding a bnAb, (ii) modify the bnAb–antigen complex chemically to render solvent-exposed surfaces non-immunogenic, and (iii) deprotect the epitope by dissociating the bnAb–antigen complex. This produces an antigen in which the only unmodified region is the epitope of the bnAb (Fig. 3). In our proof-of-concept study, using influenza hemagglutinin (HA), we demonstrated that PMD is capable of low-resolution epitope focusing.

Figure 1. Design of a universal flu vaccine by antigen reorientation. Influenza hemagglutinin (HA) is reoriented in an “upside-down” configuration to sterically occlude its head and redirect the antibody response to the more exposed stem.

Figure 2. Design of a universal Ebola vaccine candidate. Eight copies of hyperglycosylated Ebola glycoproteins (GPs) are displayed on each ferritin nanoparticle. Hyperglycosylation is used to direct antibody responses away from variable regions and toward conserved epitopes on GP.

Figure 3. Schematic of the PMD strategy. First, the epitope is protected by combining the mAb (blue hashed) with the antigen (orange). Then the surfaces of the complex are modified to render them non-immunogenic (shown as darker shading). Finally the epitope is deprotected by removal of the mAb.

PUBLICATION HIGHLIGHTS

Bringing immunofocusing into focus. (PDF)

Sriharshita Musunuri, Payton A. B. Weidenbacher, Peter S. Kim. Npj Vaccines (2024). doi.org/10.1038/s41541-023-00792-x.

Vaccine design via antigen reorientation. (PDF)

Duo Xu, Joshua J. Carter, Chunfeng Li, Ashley Utz, Payton A. B. Weidenbacher, Shaogeng Tang, Mrinmoy Sanyal, Bali Pulendran, Christopher O. Barnes, Peter S. Kim. Nature Chemical Biology (2024). doi.org/10.1038/s41589-023-01529-6.

Design of universal Ebola virus vaccine candidates via immunofocusing. (PDF)

Duo Xu, Abigail E. Powell, Ashley Utz, Mrinmoy Sanyal, Jonathan Do, J. J. Patten, Juan I. Moliva, Nancy J. Sullivan, Robert A. Davey, Peter S. Kim. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2024). doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2316960121.

Protect, Modify, Deprotect (PMD): A strategy for creating vaccines to elicit antibodies targeting a specific epitope. (PDF)

Payton A. Weidenbacher and Peter S. Kim. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2019) 116: 9947-9952.

Converting non-neutralizing antibodies into broadly

neutralizing antibodies

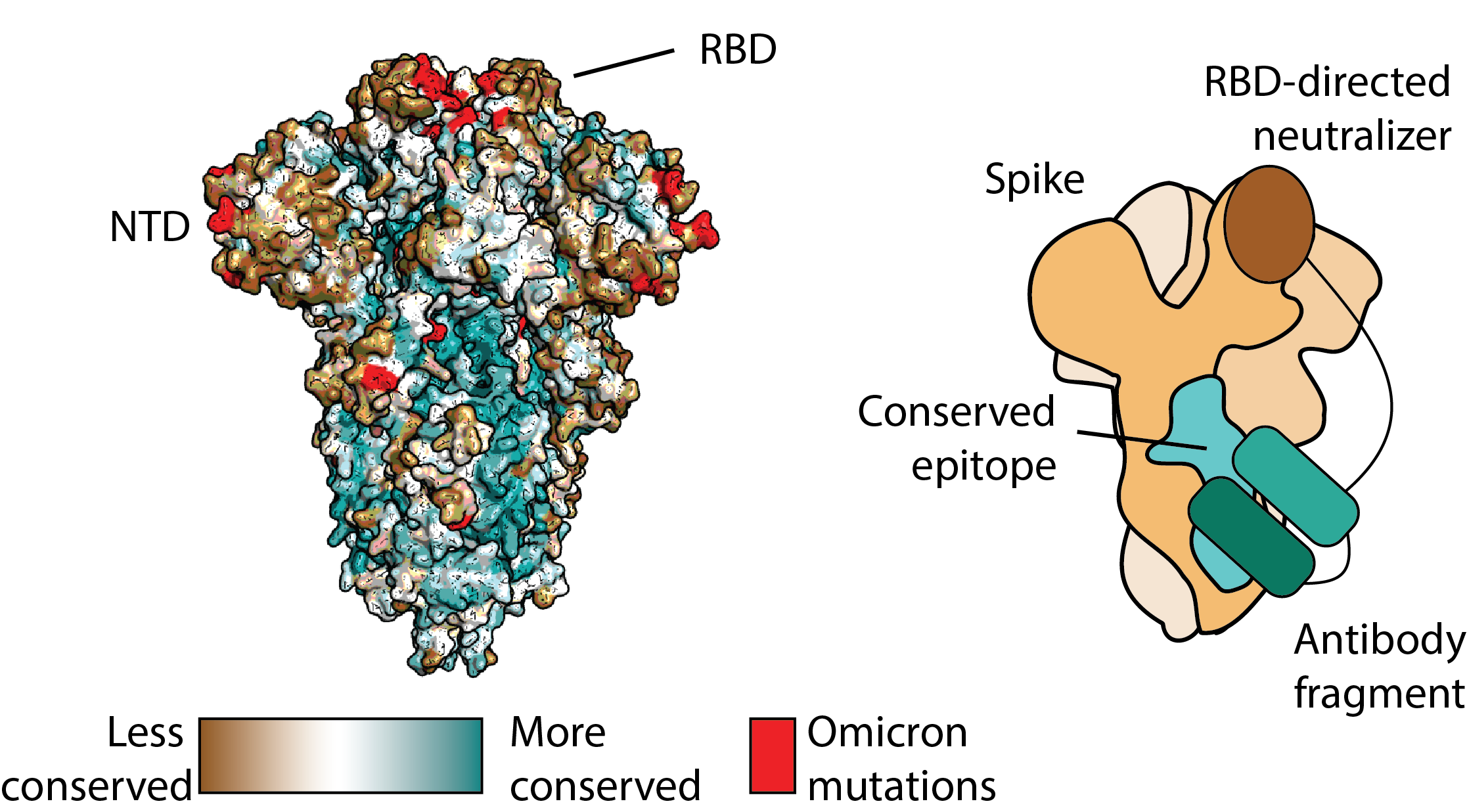

The discovery of broadly neutralizing coronavirus antibodies has been challenging. For SARS-CoV-2, most neutralizing activity comes from antibodies that target the receptor binding domain (RBD) or N-terminal domain (NTD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The RBD and NTD regions are not highly conserved within related coronavirus spike proteins. There are, however, large, conserved epitopes within the spike protein (Fig. 4 – left, blue). No potent neutralizing antibodies have been found against these epitopes. Indeed, these epitopes are generally the target of non-neutralizing antibodies.

We have generated receptor-blocking conserved non-neutralizing Antibodies (ReconnAbs), which are able to convert these non-neutralizing, cross-reactive antibodies into broad spectrum inhibitors by fusion to an RBD-directed neutralizing component (Fig. 4 – right). By targeting highly-conserved epitopes, ReconnAbs show potent activity against all SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs), including Omicron, and are likely to retain their activity against future VOCs. We envision that ReconnAbs as a new class of potent, broad-spectrum anti-viral agents.

Figure 4. Converting non-neutralizing antibodies into broadly neutralizing antibodies.

PUBLIcation highlights

Converting non-neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 antibodies targeting conserved epitopes into broad-spectrum inhibitors through receptor blockade. (PDF)

Payton A.-B. Weidenbacher, Eric Waltari, Izumi de los Rios Kobara, Benjamin N. Bell, John E. Pak, Peter S. Kim. Nature Chemical Biology (2022).

Protein language models for understanding and guiding evolution

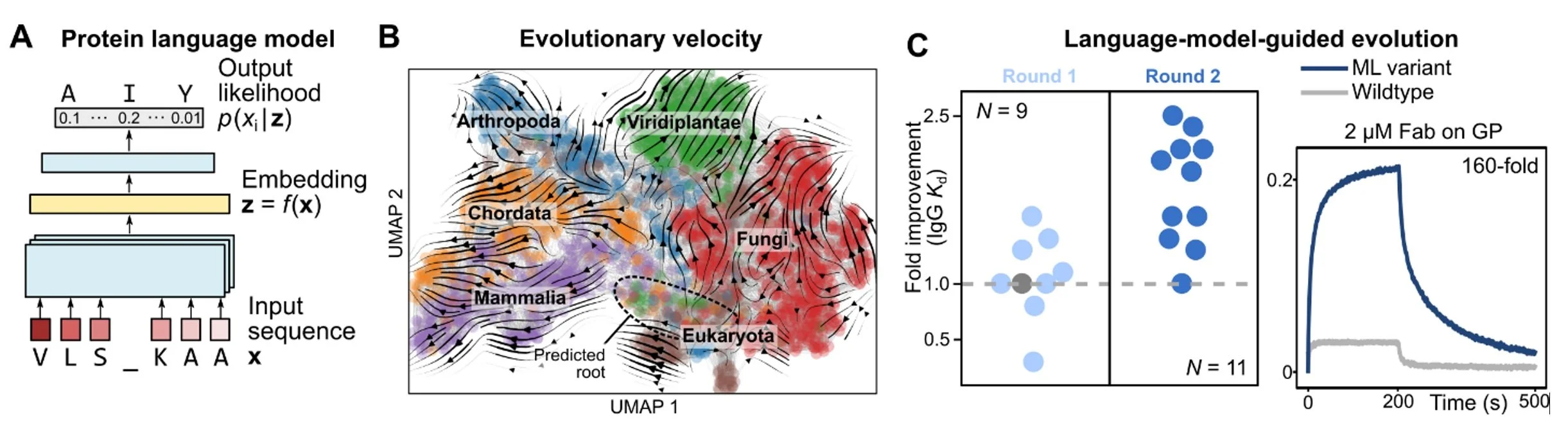

Nature is the most powerful protein engineer, and evolution is nature’s design process. We have been using machine learning algorithms to better understand the rules of natural protein evolution, with the ultimate goal of designing better proteins. We leverage sophisticated algorithms called neural language models that can learn evolutionary patterns from millions of natural protein sequences (Fig. 5A).

To demonstrate that language models can learn evolution, we first apply them to the task of predicting evolutionary dynamics, which has diverse applications that range from tracing the progression of viral outbreaks to understanding the history of life on earth. Our main conceptual advance is to reconstruct a global landscape of protein evolution through local evolutionary predictions that we refer to as evolutionary velocity (evo-velocity), which predicts the direction of evolution in landscapes of viral proteins evolving over years and of eukaryotic proteins evolving over geologic eons (Fig. 5B).

The same ideas can also be used to design new proteins. By testing mutations with higher language-model likelihood than wildtype (i.e., with positive “evolutionary velocity”), we find a surprisingly large number of variants with improved fitness. This enables highly efficient, machine-learning-guided antibody affinity maturation against diverse viral antigens, without providing the model with knowledge of the antigen, protein structure, or task-specific training data (Fig. 5C), and may also inform the design of other types of proteins as well.

Figure 5. (A) A language model learns the likelihood of an amino-acid residue occurring within a sequence context. When trained on millions of protein sequences, a large language model can capture the evolutionary “rules” governing which combinations of amino acids are more likely to appear with each other. (B) An evolutionary landscape can be approximated by a composition of local evolutionary predictions made by a language model, which we refer to as evo-velocity. Evo-velocity can predict the directionality of evolution; for example, evo-velocity analysis of the landscape of cytochrome c sequences recovers the order of various taxonomic classes in the fossil record. (C) Language models can also help guide evolution. By selecting mutations with higher language-model-likelihood than wildtype, we find many that also improve protein function under specific notions of fitness. In particular, we use language models to guide structure- and antigen-agnostic antibody affinity maturation against diverse viral antigens.

PUBLIcation highlights

Inverse folding of protein complexes with a structure-informed language model enables unsupervised antibody evolution.

Varun R. Shanker, Theodora U.J. Bruun, Brian L. Hie, Peter S. Kim. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.19.572475 bioRxiv (2023).

Efficient evolution of human antibodies from general protein language models. (PDF)

Brian L. Hie, Varun R. Shanker, Duo Xu, Theodora U. J. Bruun, Payton A. Weidenbacher, Shaogeng Tang, Wesley Wu, John E. Pak, Peter S. Kim. Nature Biotechnology (2023). doi.org/10.1038/s41587-023-01763-2.

Evolutionary velocity with protein language models predicts evolutionary dynamics of diverse proteins. (PDF)

Brian L.Hie, Kevin K. Yang, Peter S.Kim. Cell Systems (2022).

The gp41 pre-hairpin intermediate as a potential vaccine target

Despite over 3 decades of intense research, a prophylactic HIV/AIDS vaccine is not in sight. Most antibody-directed HIV-vaccine efforts target the native gp120/gp41 Env protein. In contrast, we are pursuing strategies to create novel HIV-1 vaccines that elicit antibodies against a therapeutically validated form of Env that is critical for HIV-1 infection – the pre-hairpin intermediate (PHI).

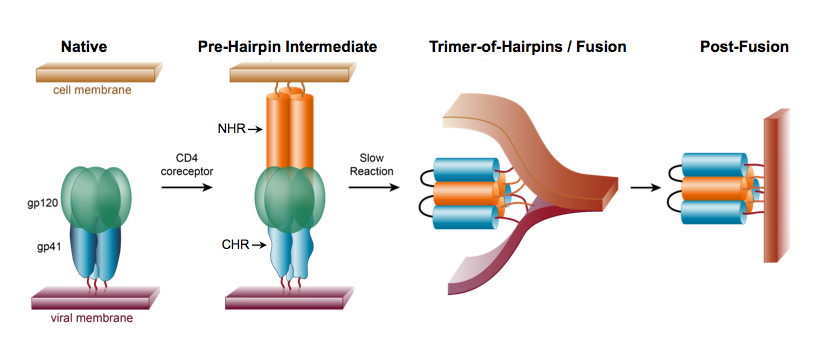

Enveloped viruses such as HIV-1 are characterized by a lipid bilayer that surrounds the nucleocapsid. To infect a cell, the membrane surrounding the virus must fuse with the membrane surrounding the host cell (Fig. 6). This membrane-fusion process is mediated by virally encoded, transmembrane-anchored glycoproteins. The mature HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein consists of two parts: a surface protein (SU) called gp120 and a transmembrane protein (TM) called gp41. On the virus surface, these glycoproteins exist as a trimer of gp120/gp41 heterodimers (Fig. 7).

Figure 6. Membrane fusion of an enveloped virus and its target cell.

Figure 7. Schematic of membrane fusion mediated by the HIV-1 gp120/gp41 Envelope glycoprotein

Figure 8. The pre-hairpin intermediate (PHI). The N-heptad repeat (NHR) and C-heptad repeat (CHR) regions are indicated. Different inhibitors work by binding to various regions of the PHI, thereby preventing formation of the trimer-of-hairpins. (review: Eckert & Kim [2001] Ann. Rev. Biochem.)

Interactions between gp120 on the virus and CD4 receptors on target cells mediate attachment of HIV-1 to CD4+ T cells. This binding event induces a conformational change in gp120 that facilitates additional interactions between gp120 with co-receptors (CCR5 or CXCR4), leading to a dramatic “spring-loaded” conformational change in gp41 (Fig. 7). As a result, gp41 adopts a pre-hairpin intermediate (PHI) conformation, in which the protein is associated with two membranes simultaneously: the host cell membrane via the “fusion peptide”, and the viral membrane via the transmembrane domain (Fig. 7). Interactions between the N-heptad repeat (NHR) and C-heptad repeat (CHR) regions (orange and blue, respectively, in Fig. 7) lead to the formation of a “trimer-of hairpins,” or six-helix bundle, which brings the two membranes together.

Peptides that bind to the NHR region of the PHI disrupt fusion by preventing formation of the trimer-of-hairpins. Such inhibitors include the C-peptides, derived from the CHR region (Fig. 8). Importantly, the FDA-approved HIV-1 drug enfuvirtide (Fuzeon™) is a C-peptide. Thus, the PHI is a validated drug target in humans.

We aim to generate a vaccine that will elicit antibodies that, like enfuvirtide, will bind to the PHI and prevent HIV-1 infection by inhibiting formation of the trimer-of-hairpins (Fig. 9). An attractive feature of the NHR region of the PHI as a target for vaccine development is that it is very highly conserved among different HIV-1 strains, so antibody-escape mutants are predicted to be less frequent than for other regions of the gp120/gp41 envelope protein.

Figure 9. An HIV vaccine approach based on eliciting antibodies that bind to the pre-hairpin intermediate (Eckert et al. [1999] Cell).

Because the PHI is transient, eliciting an immune response requires engineering of stable “mimetics” of the PHI to serve as immunogens. Using such PHI mimetics, we and others have elicited polyclonal antibody responses against the NHR region of the PHI. The resultant antisera inhibit HIV infection in cell culture, although the neutralization responses are weak. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that bind to the gp41 NHR region and inhibit HIV-1 infection in cell culture have been isolated by us and others. Crystal structures for a few of these mAbs have been determined and, in each case, the mAb binds to a prominent pocket on gp41 (Fig. 10).

As with the polyclonal antibody responses, the neutralization potencies of these mAbs are generally weak. We showed that the neutralizing activity of one of these mAbs, D5, is potentiated >5000-fold in cells that express the immunoglobulin receptor FcγRI compared to those without (Fig. 11). Further, antisera from animals immunized with PHI mimetics neutralized HIV-1 effectively in an FcγRI-dependent manner. As FcγRI is expressed on macrophages and dendritic cells, which are present at mucosal surfaces and are implicated in the early establishment of HIV-1 infection following sexual transmission, these results may be important in the development of a prophylactic HIV-1 vaccine.

Figure 10. D5, an HIV-neutralizing antibody (Miller et al. [2005] PNAS), binds to the gp41 pocket (Luftig et al. [2006] Nature Struct. Mol. Biol.)

Figure 11. Hypothesized mechanism for FcγRI -mediated potentiation of antibodies targeting the NHR region of the PHI. The Fc domain of the antibody is bound by FcγRI , similar to the previously characterized mechanism of FcγRI -mediated potentiation of antibodies targeting the MPER.

publication highlights

Structure-guided stabilization improves the ability of the HIV-1 gp41 hydrophobic pocket to elicit neutralizing antibodies. (PDF)

Theodora U. J. Bruun, Shaogeng Tang, Graham Erwin, Lindsay Deis, Daniel Fernandez, Peter S. Kim. Journal of Biological Chemistry (2023). doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.103062.

Enhancing HIV-1 Neutralization by Increasing the Local Concentration of Membrane-Proximal External Region-Directed Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies. (PDF)

Soohyun Kim, Maria V. Filsinger Interrante, Peter S. Kim. J Virol. (2022) 10.1128/jvi.01647-22.

HIV-1 prehairpin intermediate inhibitors show efficacy independent of neutralization tier. (PDF)

Benjamin N. Bell, Theodora U. J. Bruun, Natalia Friedland, Peter S. Kim. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2023). Feb 21;120(8) :e2215792120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2215792120.

The high-affinity immunoglobulin receptor FcγRI potentiates HIV-1 neutralization via antibodies against the gp41 N-heptad repeat. (PDF)

David C. Montefiori, Maria V. Filsinger Interrante, Benjamin N. Bell, Adonis A. Rubio, Joseph G. Joyce, John W. Shiver, Celia C. LaBranche, and Peter S. Kim. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2021).

A derivative of the D5 monoclonal antibody that targets the gp41 N-heptad repeat of HIV-1 with broad tier-2 neutralizing activity (PDF)

Adonis A. Rubio, Maria V. Filsinger Interrante, Benjamin N. Bell, Clayton L. Brown, Celia C. LaBranche, David C. Montefiori, Peter S. Kim. J Virol. (2021) 95(15):e0235020.

Mechanisms of Viral Membrane Fusion and Its Inhibition. (PDF)

Debra M. Eckert and Peter S. Kim. Annu. Rev. Biochem. (2001) 70: 777-810.

SARS-CoV-2

While the rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines has been a scientific triumph, the need remains for a globally available vaccine that provides longer-lasting immunity against present and future SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs). We generated DCFHP (Delta-C70-Ferritin-HexaPro), a SARS-CoV-2 spike-functionalized, ferritin-based, protein-nanoparticle that, when formulated with aluminum hydroxide as the sole adjuvant (DCFHP-alum), elicits potent and durable neutralizing antisera in non-human primates (NHPs) against known VOCs, including Omicron BQ.1, as well as against SARS-CoV-1. Following a booster approximately one year after the initial immunization, DCFHP-alum elicits a robust anamnestic response. To enable global accessibility, we generated a cell line that can enable production of thousands of vaccine doses per liter of cell culture and showed that DCFHP-alum maintains potency for at least 14 days at temperatures exceeding standard room temperature. DCFHP-alum has potential as a highly durable booster vaccine, and as a primary vaccine for pediatric use including in infants.

The intellectual property behind DCFHP has been licensed by Stanford University and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub to a commercial entity that is preparing to conduct clinical trials with DCFHP-alum.

We aim to understand a key outstanding basic science question: how does DCFHP-alum elicit durable, broad-spectrum neutralizing activity? Our approaches include characterization of the epitopes and the immunodominance of neutralizing antibodies in serum samples from NHPs and mice immunized with DCFHP-alum. We are also interrogating the B cell repertoires, for both plasma and memory B cells, at various times following immunization. We seek to identify key mAbs that allow for a detailed understanding of broad neutralization activity against VOCs.

Figure 12. A structural representation depicting a 24-subunit nanoparticle SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The figure is based on the H. pylori ferritin crystal structure (rust, PDB 3BVE) and the spike trimer cryo-EM structure (blue, PDB 6VXX). The receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein is highlighted in dark blue.

publication highlights

A ferritin-based COVID-19 nanoparticle vaccine that elicits robust, durable, broad-spectrum neutralizing antisera in non-human primates. (PDF)

Payton A.-B. Weidenbacher, Mrinmoy Sanyal, Natalia Friedland, Shaogeng Tang, Prabhu S. Arunachalam, Mengyun Hu, Ozan S. Kumru, Mary Kate Morris, Jane Fontenot, Lisa Shirreff, Jonathan Do, Ya-Chen Cheng, Gayathri Vasudevan, Mark B. Feinberg, Francois J. Villinger, Carl Hanson, Sangeeta B. Joshi, David B. Volkin, Bali Pulendran, Peter S. Kim. Nature Communications (2023). 2022 Dec 26:2022.12.25.521784. doi: 10.1101/2022.12.25.521784.

Formulation development and comparability studies with an aluminum-salt adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 Spike ferritin nanoparticle vaccine antigen produced from two different cell lines. (PDF)

Ozan Kumru, Mrinmoy Sanyal, Natalia Friedland, John Hickey, Richa Joshi, Payton Weidenbacher, Jonathan Do, Ya-Chen Cheng, Peter S. Kim, Sangeeta B Joshi, David B Volkin. Vaccine (2023). 2023 Oct 20;41(44):6502-6513. doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.08.037.

Decreased efficacy of a COVID-19 vaccine due to mutations present in early SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern.

Payton A Weidenbacher, Natalia Friedland, Mrinmoy Sanyal, Mary Kate Morris, Jonathan Do, Carl Hanson, Peter S. Kim.

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.06.27.546764v2 bioRxiv (2023).

A single immunization with spike-functionalized ferritin vaccines elicits neutralizing antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 in mice. (PDF)

Abigail E. Powell, Kaiming Zhang, Mrinmoy Sanyal, Shaogeng Tang, Payton A. Weidenbacher, Shanshan Li, Tho D. Pham, John E. Pak, Wah Chiu, Peter S. Kim. ACS Cent. Sci. (2021). 2021 Jan 27;7(1):183-199. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01405.

![Figure 5. The pre-hairpin intermediate (PHI). The N-heptad repeat (NHR) and C-heptad repeat (CHR) regions are indicated. Different inhibitors work by binding to various regions of the PHI, thereby preventing formation of the trimer-of-hairpins. (review: Eckert & Kim [2001] Ann. Rev. Biochem.)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/562d385fe4b0e2b30b0c79b4/1568155098447-XE8WL1883KKTBO51JE2N/Figure+4.png)

![Figure 6. An HIV vaccine approach based on eliciting antibodies that bind to the pre-hairpin intermediate (Eckert et al. [1999] Cell).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/562d385fe4b0e2b30b0c79b4/1568156497151-Q6CCLS4WT78OZLAU5YDM/Figure+7.png)

![Figure 7. D5, an HIV-neutralizing antibody (Miller et al. [2005] PNAS), binds to the gp41 pocket (Luftig et al. [2006] Nature Struct. Mol. Biol.)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/562d385fe4b0e2b30b0c79b4/1568156674395-LTY714PGXYDPEXK7I7W8/Figure+8.png)